CLICK HERE FOR PART 1

5. Is there life after death?

Before everyone gets excited, this is not a suggestion that we'll all end up strumming harps on some fluffy white cloud, or find ourselves shoveling coal in the depths of Hell for eternity. Because we cannot ask the dead if there's anything on the other side, we're left guessing as to what happens next. Materialists assume that there's no life after death, but it's just that — an assumption that cannot necessarily be proven. Looking closer at the machinations of the universe (or multiverse), whether it be through a classical Newtonian/Einsteinian lens, or through the spooky filter of quantum mechanics, there's no reason to believe that we only have one shot at this thing called life. It's a question of metaphysics and the possibility that the cosmos (what Carl Sagan described as "all that is or ever was or ever will be") cycles and percolates in such a way that lives are infinitely recycled. Hans Moravec put it best when, speaking in relation to the quantum Many Worlds Interpretation, said that non-observance of the universe is impossible; we must always find ourselves alive and observing the universe in some form or another. This is highly speculative stuff, but like the God problem, is one that science cannot yet tackle, leaving it to the philosophers.

6. Can you really experience anything objectively?

There's a difference between understanding the world objectively (or at least trying to, anyway) and experiencing it through an exclusively objective framework. This is essentially the problem of qualia — the notion that our surroundings can only be observed through the filter of our senses and the cogitations of our minds. Everything you know, everything you've touched, seen, and smelled, has been filtered through any number of physiological and cognitive processes. Subsequently, your subjective experience of the world is unique. In the classic example, the subjective appreciation of the color red may vary from person to person. The only way you could possibly know is if you were to somehow observe the universe from the "conscious lens" of another person in a sort ofBeing John Malkovich kind of way — not anything we're likely going to be able to accomplish at any stage of our scientific or technological development. Another way of saying all this is that the universe can only be observed through a brain (or potentially a machine mind), and by virtue of that, can only be interpreted subjectively. But given that the universe appears to be coherent and (somewhat) knowable, should we continue to assume that its true objective quality can never be observed or known? It's worth noting that much of Buddhist philosophy is predicated on this fundamental limitation (what they call emptiness), and a complete antithesis to Plato's idealism.

7. What is the best moral system?

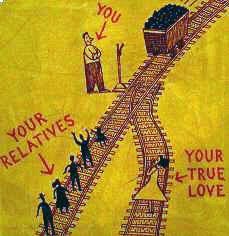

Essentially, we'll never truly be able to distinguish between "right" and "wrong" actions. At any given time in history, however, philosophers, theologians, and politicians will claim to have discovered the best way to evaluate human actions and establish the most righteous code of conduct. But it's never that easy. Life is far too messy and complicated for there to be anything like a universal morality or an absolutist ethics. The Golden Rule is great (the idea that you should treat others as you would like them to treat you), but it disregards moral autonomy and leaves no room for the imposition of justice (such as jailing criminals), and can even be used to justify oppression (Immanuel Kant was among its most staunchest critics). Moreover, it's a highly simplified rule of thumb that doesn't provision for more complex scenarios. For example, should the few be spared to save the many? Who has more moral worth: a human baby or a full-grown great ape? And as neuroscientists have shown, morality is not only a culturally-ingrained thing, it's also a part of our psychologies (the Trolly Problem is the best demonstration of this). At best, we can only say that morality is normative, while acknowledging that our sense of right and wrong will change over time.

8. What are numbers?

We use numbers every day, but taking a step back, what are they, really — and why do they do such a damn good job of helping us explain the universe (such as Newtonian laws)? Mathematical structures can consist of numbers, sets, groups, and points — but are they real objects, or do they simply describe relationships that necessarily exist in all structures? Plato argued that numbers were real (it doesn't matter that you can't "see" them), but formalists insisted that they were merely formal systems (well-defined constructions of abstract thought based on math). This is essentially an ontological problem, where we're left baffled about the true nature of the universe and which aspects of it are human constructs and which are truly tangible.

No comments:

Post a Comment